By Linda Thomas

If you’ve been circling the world of inclusion body myositis for any length of time, you’ve probably heard the word biopsy spoken with a mix of reverence, dread, and frustration. It’s often described as the “gold standard” for diagnosing IBM, yet somehow many of us walk away with results that say things like inconclusive, suggestive, or consistent with but not definitive.

So let’s talk about it. What muscle biopsies actually are, how they’re done, why doctors sometimes want more than one, and the question every patient asks quietly (or not so quietly): does it hurt, and is it worth it?

What Is a Muscle Biopsy Anyway?

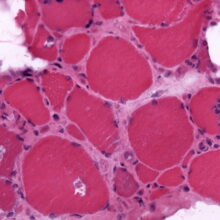

A muscle biopsy involves removing a small piece of muscle tissue so it can be examined under a microscope. In IBM, doctors are looking for very specific features—things that separate it from polymyositis, dermatomyositis, or other inflammatory muscle diseases.

There are generally two ways biopsies are done:

- Needle biopsy – A thick needle removes a small core of muscle. Less invasive, quicker healing, but sometimes too small to tell the full story.

- Open biopsy – A small incision is made, and a larger piece of muscle is taken. More tissue means more information, but also more recovery.

Neither option is “fun,” but both are common and usually done under local anesthesia.

Do They Hurt?

Short answer: yes, but usually not the way you fear.

During the procedure, the area is numbed. You may feel pressure, tugging, or an unsettling awareness that something is happening—but not sharp pain. Afterward, though, there’s soreness. Think deep bruise meets overworked muscle. Some people bounce back in days; others feel it for weeks, especially if the muscle was already weak.

What hurts more, honestly, is the waiting. Waiting for results. Waiting to see if this painful step actually brought clarity—or just more questions.

How Are Biopsies Read?

Once the muscle sample is taken, a specialized pathologist examines it using several stains and techniques. In IBM, they’re looking for a combination of features, including:

- Inflammatory cells invading muscle fibers

- Rimmed vacuoles (little “holes” inside muscle cells)

- Protein aggregates (like clumps of amyloid or TDP-43)

- Mitochondrial abnormalities

Here’s the tricky part: IBM doesn’t always show all of these features at once, especially early in the disease.

Which leads us to…

Why Are So Many Biopsies “Inconclusive”?

Because IBM is a master of hide-and-seek.

Early in the disease, inflammation may be present without the classic degenerative changes. Later, degeneration may dominate with less inflammation. If the biopsy samples the “wrong” muscle—or a muscle that’s too far gone or not affected enough—the hallmark signs can be missed.

Add to that:

- Variability in pathologist experience with IBM

- Differences in lab techniques

- Small sample sizes (especially with needle biopsies)

And suddenly, “inconclusive” starts to feel less like a failure and more like an unfortunate reality of a rare, slow-moving disease.

Why Would Anyone Do More Than One Biopsy?

This feels almost cruel when you first hear it. You want to do this again?

But there is a rationale.

IBM evolves over time. A biopsy done early may look like polymyositis. A biopsy done later may finally reveal rimmed vacuoles and protein deposits. Sometimes a second biopsy—taken from a different muscle or years later—provides the confirmation that guides treatment decisions, disability documentation, clinical trial eligibility, or simply peace of mind.

That doesn’t mean everyone should have multiple biopsies. It means the decision should be individualized, thoughtful, and worth the cost—physical and emotional.

Is It Worth It?

That’s the most personal question of all.

For some, a biopsy provides clarity after years of uncertainty. For others, it confirms what they already knew in their bones—literally. And for some, it adds another scar without adding answers.

A biopsy is worth it if:

- The result will change management or access to care

- You need diagnostic certainty for benefits, clinical trials, or treatment decisions

- You’re early in the disease and differentiation truly matters

It may not be worth it if:

- The clinical picture already clearly fits IBM

- The risks outweigh the potential benefit

- You’re being pushed toward it “just to be sure” without a clear purpose

You are allowed to ask: What will this change? And you are allowed to say no.

The Bigger Picture

Biopsies are tools—not verdicts. In IBM, they are one piece of a puzzle that also includes clinical symptoms, progression over time, imaging, blood work, and lived experience.

If your biopsy was inconclusive, you didn’t fail.

If your doctor seems unsure, they aren’t incompetent—just navigating a disease that refuses to follow neat rules.

And if you’re weighing whether to do one at all, you deserve a full conversation, not a rushed recommendation.

IBM teaches us patience we never asked for. Muscle biopsies are part of that lesson—for better or worse.

And sometimes, the bravest thing we do isn’t saying yes to another procedure…it’s asking whether we really need it.

A Gentle Case for Better Diagnostic Standards

One of the quiet truths about living with a rare disease like IBM is that we often become part of the evidence. Our bodies, our timelines, our “inconclusive” reports—they all get folded into a system that is still learning as it goes. Muscle biopsies were never meant to carry the entire weight of diagnosis, yet for many rare diseases, they still do.

Improving diagnostic standards doesn’t mean abandoning biopsies. It means contextualizing them. It means combining pathology with longitudinal observation, advanced imaging, functional assessments, and—most importantly—listening to patients who have lived in these bodies for years. It means acknowledging that a single snapshot of muscle tissue may not capture a disease that unfolds slowly, unevenly, and unpredictably.

Rare disease patients pay a unique price when diagnostic tools fall short. Delays mean missed opportunities for support, inappropriate treatments, and years spent doubting what we already know to be true. When a biopsy comes back “inconclusive,” the burden often shifts to the patient to prove they are still struggling—still declining—still worthy of answers.

Advocacy doesn’t always look like rallies or petitions. Sometimes it looks like sharing our stories, asking better questions in exam rooms, supporting research that reflects the real course of disease, and pushing—gently but persistently—for diagnostic criteria that evolve alongside medical understanding.

If we want better outcomes for rare diseases, we need better frameworks for recognizing them. Not perfect certainty. Just enough clarity, compassion, and humility to meet patients where they are.

Because when diagnosis improves, everything that follows—care, research, dignity—has a better chance of improving too. of the subjects you would include. Just in case, here it is.

Linda Thomas was diagnosed with IBM in 2023. Her disease has progressed slowly so far. She journals about her journey in a blog at ibmwarrior.com and has written three books on self improvement. After several jobs in leadership positions, she failed retirement three times but is now getting the hang of it.

I was diagnosed with IBM in 2023. It has changed my life and my family’s. I have a wonderful doctor and the team he put together has given me many tools to work with. I have tried journaling many times but just give up. I going too think about giving it another try.

Thank you for addressing the biopsy v no biopsy conundrum. I wish I had had this information at the time I was diagnosed in 2015. My biopsies will always be a source of trauma that could have been mitigated had I known what questions to ask. Most importantly, I would have insisted on sedation. My second biopsy was taken at a nationally recognized mitosis center so I trusted them. Not only was sedation not offered but, I was in fact told having sedation would affect the samples themselves. They took 4 (maybe 5) strips of muscle tissue. They stopped when I was “in trouble”. I hope that someday diagnostic methods and lab standards will be standardized.

I was diagnosed with IBM in 2019 after a muscle biopsy along with other neurological tests confirmed the diagnosis. Since then I had another to confirm the IBM when I became a patient at Johns Hopkins. I then had a MRI guided muscle biopsy for research purposes. Each biopsy didn’t hurt as they numb the area and the procedure doesn’t last too long. My philosophy is that if the biopsy helps to confirm the IBM diagnosis then go for it.